“We must open the doors and we must see to it they remain open, so that others can pass through.” – Rosemary Brown

During the month of February we as a community come together to recognize the important and lasting contributions of people of African and Caribbean descent in Canada. It is also time for us to be aware of the history we are writing now and what we can do to build a better future of which we can be proud.

Black History Month is a time where we reflect, and highlight the stories, lessons, struggles and accomplishments of Canadians of African and Caribbean descent. Although I recognize how far we have come as a community, it is important that we also recognize past injustices to Black Canadian on our path towards reconciliation.

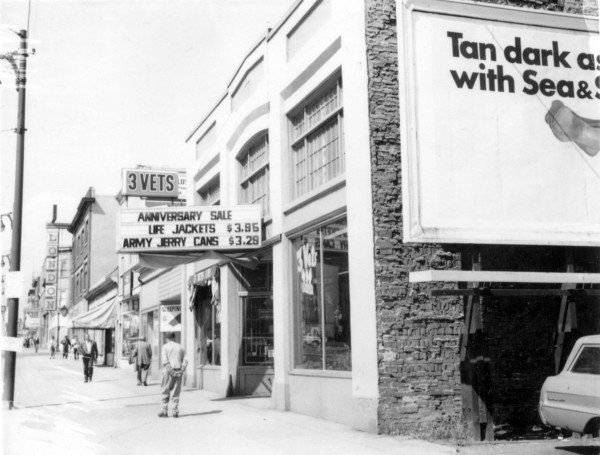

The first black immigrants arrived in British Columbia from California in 1858, but began migrating to Vancouver in the early 1900s, making their homes in Vancouver, on Canada’s west coast. On the southwestern edge of the neighbourhood of Strathcona, there was T-shaped intersection alongside it a small, four block long alleyway. This intersection and alleyway was historically known as Hogan’s Alley.

It was known as a vibrant destination for food and jazz and was the heart of the first black community in British Columbia. It was home to black cultural institutions which famously included Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, and African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel. The church was the product of fundraising efforts by prominent members of the growing community such as Nora Hendrix, the grandmother to rock legend Jimi Hendrix.

832 Main Street in Hogan’s Alley, 1969, Vancouver, B.C. Image: City of Vancouver Archives/CVA203-18-832 – CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES

Unfortunately, from the 1930s onward, in Vancouver, British Columbia the Black Canadian community was gradually being displaced in the city’s attempt at urban renewal. The displacement of the community was part of a larger strategy to make commuting from the predominantly white suburbs of the Lower Mainland less taxing. In 1972 the construction of the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts displaced the heart of the once vibrant Black Canadian community. It represented more than a loss of a geographical center for the community, it created a long-term and ongoing impact to the economic prosperity, and social well-being of Black Canadians in the region. Despite the City of Vancouver’s systemic erasure of the community at that time, Black Canadians in British Columbia have continued to succeed and triumph.

Unfortunately, today many Black Canadians continue to face racism, inequality, and discrimination as part of their daily lives. As lawmakers, as community members, and as Canadians, we will continue work together to break down these barriers and strive towards a stronger, more inclusive Canada.