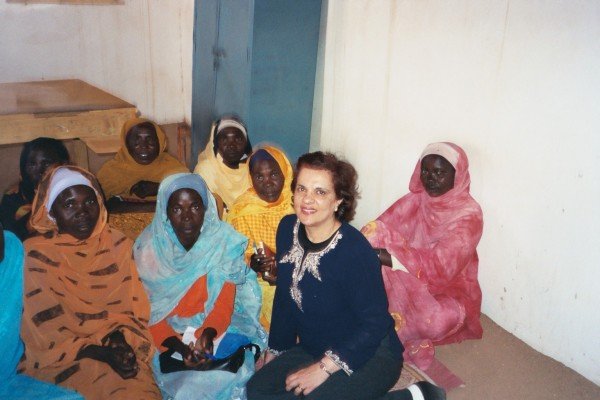

From 2002-2006 I served as Canada’s Special Envoy for Peace in Sudan. In 2004, during the height of the crisis in Darfur, I travelled to many refugee camps and witnessed first-hand the increasingly dire realities of women and girls in the region, many of whom were victims of sexual violence.

To make matters worse, these women and girls were being beaten and raped by their own government’s militia.

There is one day which I still remember vividly. I was in a refugee camp in Nyala where I saw a young girl being brought to the refugee camp in a wheelbarrow. While she was out collecting firewood, a common chore for young girls, she had been raped and brutally beaten.

Earlier I had met with the Governor of Nyala and he would not accept that women and girls were being raped by the government militia. When I presented to him the case of the young 13-year-old girl who was raped and beaten he finally recognized the severity of the situation and agreed to bring the armed forced together. Following this meeting, a new protocol was put in place where members of Canada’s Royal Canadian Mounted Police came in and taught local forces how to properly investigate rape cases and talked to hospital staff about administering rape kits. They also saw to it that young girls would have security staff accompany them when they went to collect firewood, however this rarely ended up being the case.

It is well documented that the gender violence committed on the women and girls in Darfur was horrendous. For me when I met the mothers of the young girls who were raped I was lost for words. What can one possibly say to a mother of a young girl who was gang-raped and violated? How can you find the words to heal such pain?

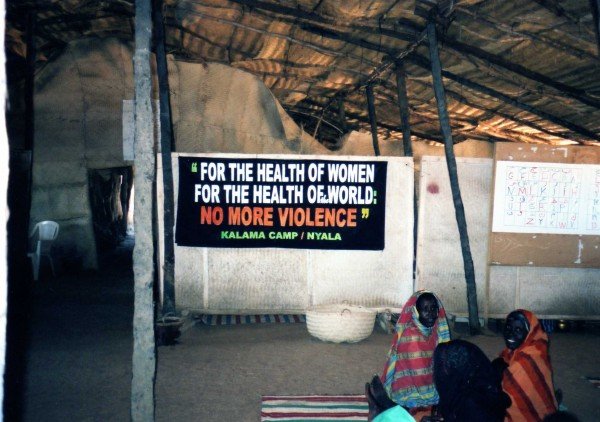

Women in Sudan have worked very hard and have conducted many campaigns to change the rape laws.

In 2009, the Salmmah Women’s Resource Centre and other women’s activist groups launched a legal campaign to change the country’s rape laws as the Sharia-based Criminal Act of 1991 treated rape as if it was as intercourse outside the marriage making it difficult to prosecute the crime of rape.

Sadly, anyone who had been raped would be considered guilty of intercourse outside of marriage, a crime punishable by stoning to death if married or 100 lashes if unmarried. This Sudanese law made it particularly difficult to prosecute sexual violence in the Darfur conflict. Also, it was very difficult to prosecute as there was a complete denial of the crime by the authorities.

Following many years of activism and advocacy by women in February 2015, this rape law was reformed, making it possible for a woman to accuse a man of rape without her being accused of intercourse outside of marriage.

There is still a lot of work to be done in the Sudan to protect women and girls. How does one erase years of gender violence?

I will never forget the eyes of the thirteen-year-old that was brought to the camp in the wheelbarrow.

Her pain.

Her fear.

Tears running down her cheeks.

Her tears may have dried, but her pain and fear will always exist. I will never forget.